The Death of Little Things

The saddest part of growing up and becoming responsible is not the death of the little things that used to make up your life but the knowledge that the person you were has gone forever, disappeared before you know how to be the person you're going to become.

For me, those little things that made up the person I was are tied in with pubs.

I'm nearly twenty-six now and teetotal, but I began drinking at fourteen and by fifteen I was drinking around the pubs of Chester. After lessons had finished at school, me and my mate Matt would change quickly in the toilets and head out for a pint. I think everybody knew what we were doing; like most kids of that age, we were pretending to be grown-ups.

So while I was experienced at pubs by the age of eighteen, it wasn't until I began working in The Stag in Warrington that I began my education in pubs.

The Stag is on Chester Road on the way into Warrington, sitting on the corner between a mini-market and the swing bridge over the Manchester Ship Canal. There's a bowling green outside, and inside the building there's both a lounge and a bar. When I worked there in 2000, the busiest day was Sunday when families came in for Sunday lunch.

Working there was me, Jane, Dave, the chefs Pete and Duncan and the managers Alf and Ilona. I began as a waiter on the Sundays, taking food orders, preparing the plates for the chefs and serving the food. When Dave found out I was eighteen, he trained me to pull a pint behind the bar, starting off with the lagers like Carling and Kronenbourg, then the handpulled bitters before teaching me the secret of bar work: the Guinness advert is nonsense; you don't have to wait ninety seconds to pull one as the black stuff pours like a normal pint.

When Dave left, I ended up working the bar full-time, doing a split shift between eleven and two, then coming back to work from five till close. Cycling there, I covered about twenty miles a day on my bike, sardonically nicknamed 'The Beast'.

It was while at The Stag that I was introduced to the concept of the lock-in. The lock-in is a tradition that still survives despite the advent of twenty-four hour licensing in Britain, although the illegality and, therefore, the fun of it has died.

It used to be the law in British pubs that customers would have to be shown the door by 23.20. The lock-in was when the staff used to stay behind and have a drink. Occasionally, certain select customers would be invited to stay but the routine was always the same. The word would pass around the staff that a lock-in was on the cards so nobody made plans to go home or, if they had, they cancelled them. Customers invited to the lock-in would all sit in one corner of the bar, waiting for the others to leave. At no point, would anyone mention to an uninvited customer that a lock-in was going to take place, although people would have guessed. Once the customers were gone and the pub cleared and cleaned, the doors were locked, the lights doused and the curtains shut. This was to make sure that any police driving past would ostensibly be unaware of what was going on (although they would have guessed). One manager I worked for was once caught by the police being chased around one of his former pubs by an invited customer with a horsewhip. As the officers entered and asked who the manager was, someone pointed to the guy in the shirt and tie running around the bar. He ended up in court where he got a slap on the wrist. Seeing the officer outside the courtroom later, he was told, "Just close the curtains next time, mate. We know it goes on. But close the curtains."

What gave the lock-in its flavour was the feeling that, sitting downing free pint after free pint, we were raising two fingers not only to the customers that we had to wait on to get paid but to the law of the land that tried to forbid what we were doing. That feeling, the frisson of minor illegality is lost now in modern Britain . The lock-ins still go on but the feeling has disappeared.

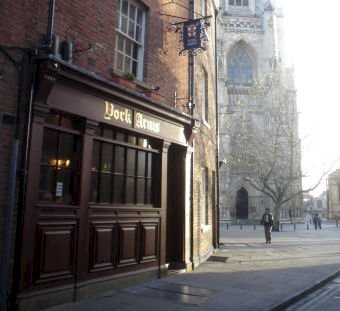

After a last minute and unplanned decision to go to university and not be a barman for the rest of my life, I ended up in York. Faced with the lack of income through the abolition of the student grant, I went looking for another bar job and ended up taking one off a guy called Bill in what looked to be an old man's pub in the shadow of the Minster called The York Arms.

If Bill didn't lie, then he certainly softened the truth. The York Arms was a gay bar in all but name. The bar side was pretty much exclusively gay, while the lounge and the snug catered for heterosexuals. It was never a conscious choice by anybody that that was the set-out; it had just evolved organically that way over time. Bizarrely, The York Arms was a family- and tourist-orientated pub during the day that became populated by sub-cultures of an evening and weekend.

After Bill left, he was replaced by Malcolm and Sandra and their son Kieran, and for the rest of that year until they left for greener pastures, Malcolm and Sandra became my surrogate parents. They were replaced by Mark and Jo, who reintroduced the lock-in to my world along with Mark's skills as a chef – "Soup? Root vegetable and a herb. Gets them every time." I met Wayne who became one of my best friends there and we ended up working together in many places after we both left The York Arms. Frankie, one of the girls who lived next door to me in university digs worked there, as did Liz, Ash, Becky and Paul. Eventually, me, Frankie and Ash went to work at Toffs nightclub and, in exchange, Kate and Tracy from Toffs went to work at the York Arms.

Since we didn't play much music at The York Arms and whatever we did play was always turned a little low, conversation dominated the smoky, blue air. And since we were cheap, cheerful and friendly, we continually attracted new regulars who became our firm friends. We had Ian, the football fan from down south who would occasionally get drunk, give Nazi salutes and goose-step from the pub; the transvestite who lived as a rough, dog-loving engineer during the week and dressed up as a 'slutty Madonna' (his words) at the weekend and Bob, who looked like a bigger Freddie Mercury, had two kids and had lived with Neil for over a decade. One New Year's Eve, I saw Bob prancing about the street in a tutu. Another time, Paul the transvestite turned up on a Saturday evening in full-drag with a newly-bought water-filled bra that all the guys checked the feel of. My girlfriend at the time, G., texted to me to see how work was and I sent back Just feeling up a transvestite's boobs at the bar. Her response was swift and simple – Good, as long as you're keeping yourself out of trouble.

I was young back then and in love, and when I finished on a Friday night, I would cycle to G's house twelve o'clock, climb into bed with her and fall asleep. Saturdays were different – they were reserved for the lock-in.

Eventually, things came to an end at The York Arms. Mark and Jo moved on and there was a succession of relief managers before we ended up with a manager who wanted to make his mark on the place. One day, I made the stupid decision of not going into work that day, and I haven't been back to The York Arms since.

By that time, I had already begun working at Toffs nightclub, which billed itself without irony as being York's premier nightspot. The dream of the pub was ending for me by then: it was too loud to speak to customers and the once that you could manage to shout to tended to be morons and fuckwits. In the strangely incestuous world of working in nightclubs where all the staff seemed to be dating each other, the lock-in was non-existent and the sense of camaraderie that had existed previously between staff and management had become a myth.

It was working in the nightclub atmosphere that soured me against drinking and drink-culture. I saw horrendous, inexcusable things: a man glassed at the bar because of a football tattoo, a fractured skull outside the door of another place, countless fights and a brawl between twenty customers and the entire door staff. I saw the worst of British life those days when people were tanked up and had developed whiskey muscles. I worked in many more bars and a social club but the magic of it was lost for me by then.

But I still love pubs, and I dream of the perfect one. It's got to be dark enough so you need to switch lamps on inside but light enough so you still see the stains in the carpet. The staff and the regulars have got to be friendly, and they have to serve proper food such as pies, roasts or giant Yorkshire puddings. The conversation has got to be serious but never hardline, and everybody should be welcome. Proper drinks will be served such as real ale, gin and whiskey. There will be no alcopops. A pool table would be welcome, but not necessary. A dartboard would be in the lounge. It all has to look well-kept but not new. And the place should be warm, especially in winter so a coal fire should burn for at least three-and-a-half months of the year.

I was reminded of these places a short while ago when I was waiting to get out of Lincoln. I was on a final road trip before the proper career I'd been holding off ensnared me. My mate Paul, another old York Arms regular, had some other business to do and so I decided to kill time in an unfamiliar city.

Wandering, I found a place called The Jailhouse that advertised itself as a rock bar. Inside, the walls were papered with faded posters of old gigs. Behind the bar was a Brummie who had somehow ended up in Lincolnshire, and the solitary customer was from Forest Gate in London. I ordered a drink and didn't have to shout over any music. I sat and drank, and talked the prices of cigarettes and petrol with the guys. They were warm and welcoming and had interesting opinions.

After half an hour, I had to leave to meet Paul. I thanked them for their time and their company and left. Outside, standing in the cold, I thought about how nice it would be to have been able to stay, drink and shoot the breeze with guys, how warm it had been inside, how the little things had died and the person I was once is now long gone.